In the early days of the web (the early

’90s), when the first HTML specification was being adopted, CSS did not

exist. Web developers and webmasters (do those even exist anymore?) were

responsible for delivering their content, design and layout in one

package. It worked great and everything was right with the world. That

is, until things became more complex. The roaring ’90s of the Internet

brought new revisions to the HTML specification and new innovations to

web browsers which allowed for increasingly complicated design elements

and content delivery methods. The ever-increasing complexity made it

more difficult to maintain consistent design across large web sites.

That’s when big stupid web design suites became popular. Software like

Microsoft FrontPage and Macromedia Dreamweaver became almost a necessity

just to maintain page templates and edit pages in a wysiwyg format.

In the early days of the web (the early

’90s), when the first HTML specification was being adopted, CSS did not

exist. Web developers and webmasters (do those even exist anymore?) were

responsible for delivering their content, design and layout in one

package. It worked great and everything was right with the world. That

is, until things became more complex. The roaring ’90s of the Internet

brought new revisions to the HTML specification and new innovations to

web browsers which allowed for increasingly complicated design elements

and content delivery methods. The ever-increasing complexity made it

more difficult to maintain consistent design across large web sites.

That’s when big stupid web design suites became popular. Software like

Microsoft FrontPage and Macromedia Dreamweaver became almost a necessity

just to maintain page templates and edit pages in a wysiwyg format.

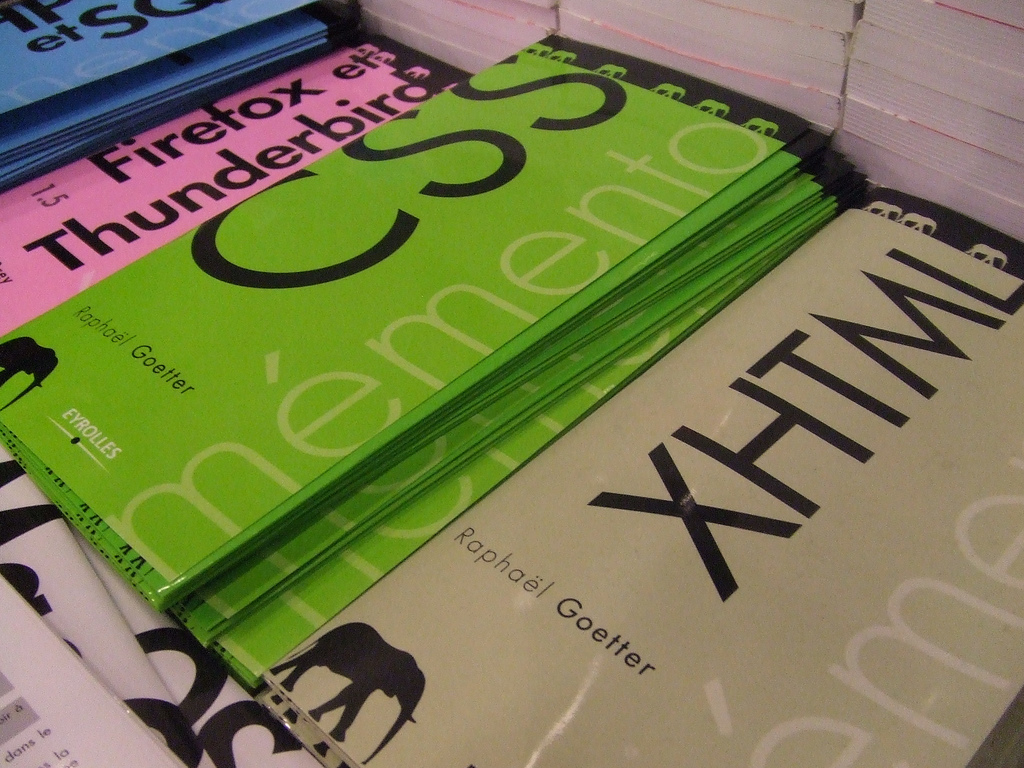

At some point, smart people got fed up with this crap and said, “Wouldn’t it be great if HTML didn’t even exist? Content could be delivered to users in an abstract format like XML and we’ll use something separate to control the design.” Following good programming practices, content and design should be completely separate beasts, and hence XHTML and CSS was born.

Unfortunately, web developers and designers had to follow a simple rule that still holds true today: If you want consistent support across all the major web browsers, you have to write your markup using old specifications. Web browser vendors also had to follow a similar rule: If you want your web browser to work against the whole of the Internet, you have to continue eternal support for the oldest specifications that still remain in use anywhere on the Internet. So the desire for consistent support from web developers and designers and browser vendors combined with a heaping helping of laziness gives us what we have today.

So instead of just blathering on for paragraphs on what good markup looks like, I’m going to break it down into a few short examples and write a short quip on each one.

-

XHTML/CSS allows you to separate your design from your content; try not to recombine them.

<strong>Bad:</strong> <span style="color: red;">Password must contain at least 6 characters</span> <strong>Good:</strong> <style type="text/css">form .error { color: red; }</style> <span class="error">Password must contain at least 6 characters</span> -

This is just as bad, if not worse, because you went through the work of separating your design from your content only to combine them again in name. If you want to change the style of this form error to another color, you still have to change the stylesheet and the markup in order for it to semantically make sense.

<strong>Bad:</strong> <style type="text/css">.red { color: red; }</style> <span class="red">Password must contain at least 6 characters</span> <strong>Good:</strong> <style type="text/css">form .error { color: red; }</style> <span class="error">Password must contain at least 6 characters</span> -

Even the oldest CSS specifications allow for inheritance, so write your markup in a way that allows you to really take advantage of that. This allows you to use the error class name in multiple contexts and specify exactly the style you want within a given context. Use inheritance.

<strong>Bad:</strong> <style type="text/css">.form-error { color: red; }</style> <span class="form-error">Password must contain at least 6 characters</span> <strong>Good:</strong> <style type="text/css">form .error { color: red; }</style> <span class="error">Password must contain at least 6 characters</span> -

Never use the font tag, its not valid XHTML and for good reason. This tag embodies exactly what XHTML is trying overcome. I know your browser will render it properly, but your browser will also render it properly using XHTML/CSS. If you are reading this and don’t understand why this is bad and you plan on continuing with this type of markup, then you should probably just stop reading here.

<strong>Bad:</strong> <font color="red">Password must contain at least 6 characters</font> -

Use valid built-in XHTML tags instead of a billion spans with custom class names. Do you think an h1 looks too big? Then make it smaller. As a side note, don’t start with h3 and use up all the headline tags down to h6 and then think you ran out. Why would you do that? Don’t want to start with an h1 just in case you need something bigger? If you need something bigger than a top level headline, then its not a headline so there’s nothing to worry about because you won’t be needing a headline tag. Start with h1 and style them all exactly how you want them. If you need more than 6, then you’re probably doing it wrong. Try using inheritance to style your headlines within a certain context instead of creating new class names.

<strong>Bad:</strong> <h3>A headline</h3> <h4>Another headline</h4> <h5>Yet Another headline</h5> <h6 class="style-a">Tired of this yet?</h6> <h6 class="i-ran-out">Headline!!</h6> <strong>Good:</strong> <h1>A headline</h1> <h2>Another headline</h2> <h3>Yet Another headline</h3> <h4>Tired of this yet?</h4> <h5>Still got one left!!</h5> -

Don’t use bold tags for the same reason you shouldn’t use font tags. Bold tags combine content and design. This one seems to be one of the most confusing for some people to grasp. I don’t know why, maybe its because b seems so much quicker than strong. The problem is, your designer might decide to change the style, and good markup will allow him to make that change by editing stylesheets alone.

<strong>Bad:</strong> <b>Some bold text</b> <strong>Good:</strong> <strong>Some possibly bold text</strong>